We all want to make smart investments, and there are many ways of doing so. One, for many probably a surprising way, is by knowing your liberal arts too. Yes, of course, traders can make money without knowing the companies and just act at Buy and Sell. But to see your money grow big time thanks to compound interest, it can take more. An interesting perspective on this is presented in “Investing: The Last Liberal Art” by Robert G Hagstrom. It is not a traditional how-to book on investing. Instead, it is more about “stock picking as a subdivision of the art of worldly wisdom.”

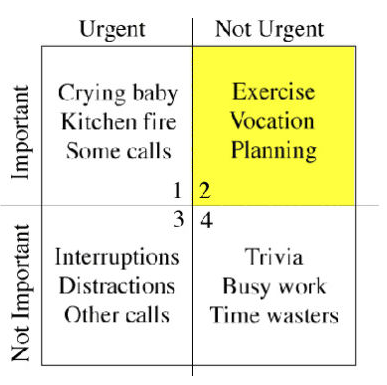

How the does the author suggest that we obtain this worldly wisdom? It happens in two broad steps:

To state the matter concisely, it is an ongoing process of, first, acquiring significant concepts—the models—from many areas of knowledge and then, second, learning to recognize patterns of similarity among them. The first is a matter of educating yourself; the second is a matter of learning to think and see differently.

To help us obtain this blissful state, Robert guides us through a set of major mental models created within physics, biology, sociology, psychology, philosophy, literature, and mathematics. They help us move into step one where we learn about everything from our biases and miscalculations, via evolutionary biology and information overload causing an illusion of knowledge, over to Kahneman’s two types of thinking, and William James’ pragmatism. Also, we should never ignore the classic books such as the Brothers Karamazov, The Great Gatsby, or To the lighthouse:

“The great works of literature have enormous power to touch our hearts and expand our minds.”

The second step, which is harder than the first but which also has a tremendous potential, lies in building a model where all these parts fit together. Based on the models you have chosen, you create a way of looking at the world and then investing accordingly. We aim to avoid Charlie Munger’s classic trap: “To a man with only a hammer, every problem looks pretty much like a nail.”

I must say I loved this book, for several reasons. One is that it shows how investing in companies can be enhanced by improving our worldly wisdom. Of course, such worldly wisdom is a gift in itself since you understand more about your place in the universe. Another reason I love this book is since it also got me to think about the lines between robot investors and people. The book didn’t mention this but given how the financial tools evolve I came to think of it.

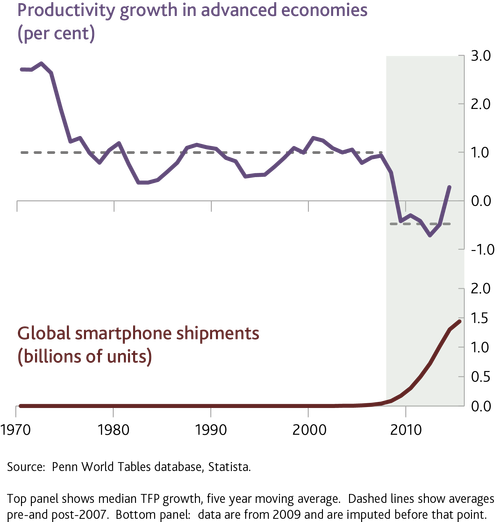

Surely, someone will state that the machines can do all the investing for us. For me, that will not be true in a long time. The reason the machines will need us? Humans are also deeply illogical, lazy, and can suffer from “dysrationalia”— which is the “inability to think and behave rationally despite having high intelligence.” Many business decisions are done based on fear, revenge, or vanity and then covered in the latest business lingo. We also base many decisions on older models such as regression to the means – what goes up must go down. This can be true in several areas but the stock market is more complex:

Stocks that are thought to be high in price can still move higher; stocks that are low in price can continue to decline. It is important to remain flexible in your thinking.

So I guess that the investment robots will do a much better job when they work alongside humans. The robots can present their investment suggestions, and then we can add a human side of it. To avoid mindware gaps, we should strive for a broad education and for checking our egos and their limitations at the door also when investing. Think you have no biases, assumptions, and always act based on reason? Don’t fool yourself. We humans are much more complex than we allow ourselves to realize, but knowing we can be both rational and illogical can be an important knowledge not only when investing, but when living. As Robert says:

“What all investors need to internalize is that they are often unaware of their bad decisions. To fully understand the markets and investing, we now know we have to understand our own irrationalities.”

So let’s accept our limitations while striving to build wordly wisdom. Not only can we invest smarter. We can also be better parents, lovers, and friends. I will let Warren Buffett end this post:

“The formula we use for evaluating stocks and businesses is identical. Indeed, the formula for valuing all assets that are purchased for financial gain has been unchanged since it was first laid out by a very smart man in about 600 B.C.E. The oracle was Aesop and his enduring, though somewhat incomplete, insight was ‘a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.’ To flesh out this principle, you must answer only three questions. How certain are you that there are indeed birds in the bush? When will they emerge and how many will there be? What is the risk-free interest rate? If you can answer these three questions, you will know the maximum value of the bush—and the maximum number of birds you now possess that should be offered for it. And, of course, don’t literally think birds. Think dollars.”

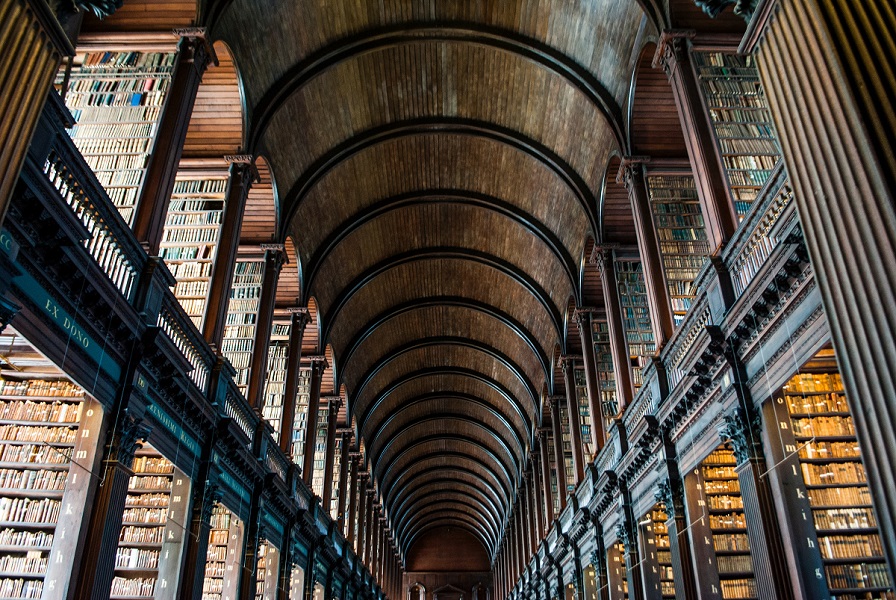

Photo by Neil Cooper on Unsplash